Dr. Farhan Hanif Siddiqi is a Professor at the School of Politics and International Relations at Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, with expertise in Pakistani politics, ethnic conflict, and South Asian geopolitics. He is the author of The Politics of Ethnicity in Pakistan: The Baloch, Sindhi, and Mohajir Ethnic Movements and has made significant contributions to the field through works such as Regional Security Dynamics in the Middle East: The Problematic Search for a Regional Leader, General Elections in Pakistan 2013: The Consolidation of Democracy, and Security Dynamics in Pakistani Balochistan: Religious Activism and Ethnic Conflict in the War on Terror.

In this interview, Dr. Siddiqi unpacks the intricate relationship between ethnicity, religion, and politics in Pakistan and details how state policies have contributed to the rise of ethnic movements and systemic violence against religious minorities.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Arshi Qureshi: How have state policies played a significant role in fueling ethnic movements in Pakistan? What is the core of the ethnic problem in Pakistan?

Dr. Farhan Siddiqi: Looking back to 1947, Pakistan was one of the first countries to experience disintegration after World War II, notably in 1971 when East Pakistan became Bangladesh. This was largely due to deep ethnic fault lines.

One of the core issues with Pakistani politics has been the lack of a stable and functioning democratic system. From 1947 to 2008, the country never experienced a consistent, fully operational democratic government.

For much of the country’s history, ethnic minorities were systematically denied the opportunity to participate in the political process. This exclusion was a major factor in the creation of Bangladesh, and it continues to fuel ethnic movements within Pakistan, including those led by the Baloch, Sindhi, Muhajir, and Pashtun communities. The denial of political rights and representation is a critical reason for the ongoing ethnic conflicts in Pakistan.

While the political aspect is central, the economic dimension is also important to consider. Economic deprivation and disempowerment have played a role in mobilizing ethnic groups, as they often link political struggles with economic inequalities. However, the political dimension remains dominant.

Another key factor is the failure of the state to clearly define what it means to be a Pakistani. If we look at the speeches of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, he presented a vision of Pakistan as a secular state where citizens, regardless of their religion, could practice freely. However, he was also clear about his stance on ethnic identity, declaring that people should no longer identify as Baloch, Sindhi, Pashtun, or Bengali, but simply as Pakistanis. The lack of recognition of ethnic identity has contributed significantly to the alienation of minority groups. This nationalist view was echoed by subsequent political and military leaders, who often adopted a securitized view of ethnic identity, dismissing or suppressing ethnic diversity.

Moreover, the failure to address the question of who constitutes a Pakistani citizen has led to the marginalization of religious minorities, such as Ahmadis, Christians, and other non-Muslims. The slogan “Pakistan ka matlab kya, la ilaha illallah” — “What is the meaning of Pakistan? There is no god but Allah” — embodies this exclusionary sentiment, which has led to the persecution of religious and ethnic minorities.

In summary, the failure of the state to define and include ethnic and religious identities within the framework of Pakistani citizenship has been a major driver of ethnic conflict and discrimination in the country.

AQ: How does the state exercise control over Ahmedis, Baloch and Sindhi populations, and how is this control a form of systemic violence?

FS: The violence faced by ethnic minorities in Pakistan, particularly the Ahmadis, is deeply structural. The state has institutionalized and normalized the blasphemy laws, embedding them within the very definition of Pakistani citizenship. Blasphemy laws are part of the Pakistan Penal Code, criminalizing acts or speech deemed offensive to Islam or disrespectful towards Prophet Muhammad. These laws are broad and vague, it allows a wide range of interpretations, which makes it easier for anyone to be accused. The normalization of this discourse, backed by state elites, creates a climate of systemic violence.

This rise of majoritarianism is one of the most pressing challenges in Pakistan’s present and future realities. When it comes to ethnic minorities, the state’s approach has been primarily coercive. The state has not taken a more accommodating or compromising stance towards groups such as the Bengalis, Sindhis, Muhajirs, Pashtuns, or Baloch. Whenever these groups have protested due to the denial of political, economic, or other rights, the state has only responded to the violence without addressing the root causes.

Pakistan has not adequately addressed the grievances of its ethnic minorities because it fails to engage with discourses coming from the periphery — those who experience marginalization. The state’s inability to recognize these claims has perpetuated systemic violence and the further alienation of these communities.

AQ: Do you think the rise in violence is a result of state policies, and do movements and protests by ethnic minorities have any impact on the government and its policies?

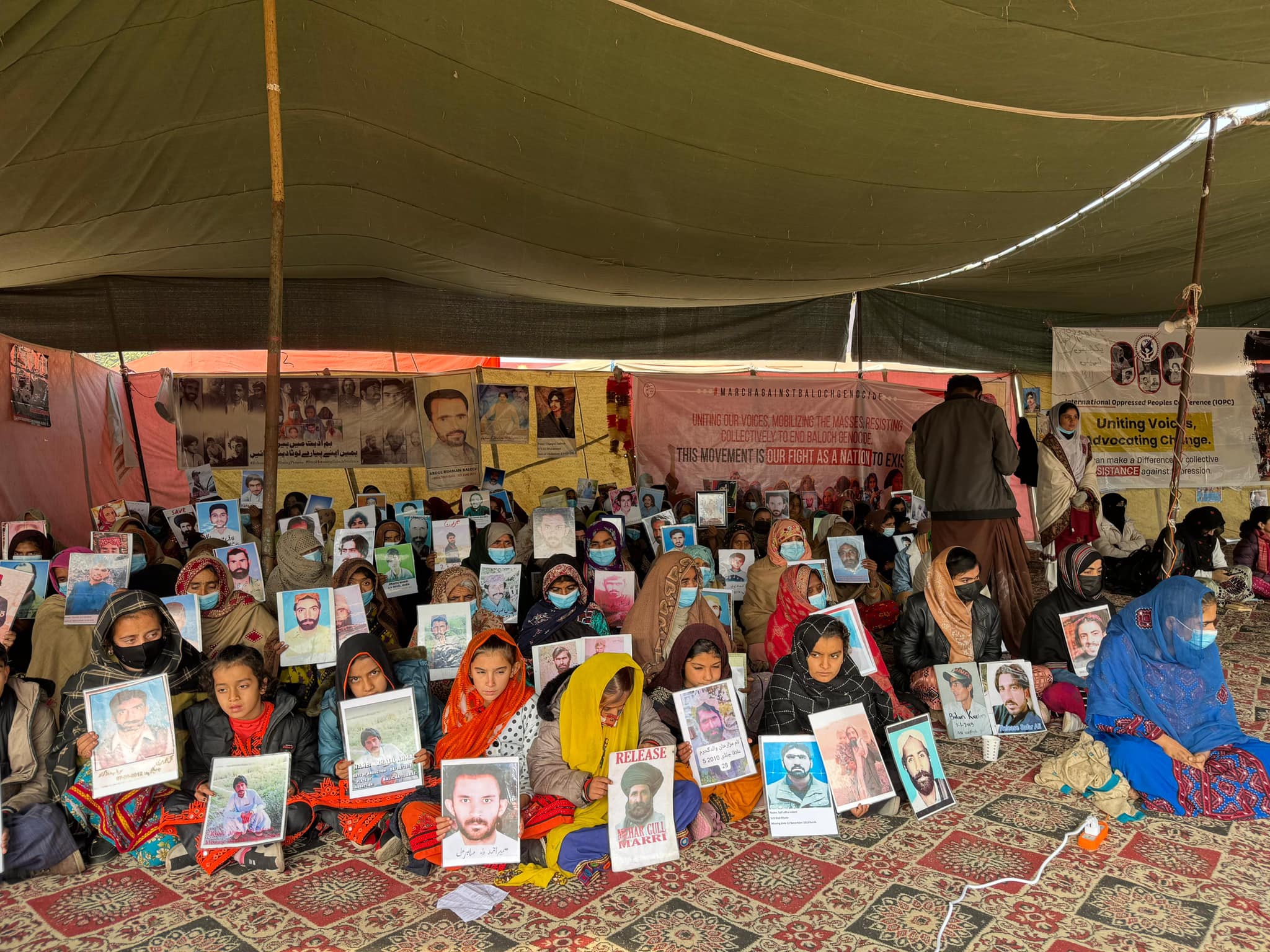

FS: Balochistan is now in its fifth phase of insurgency. The first phase started in the 1940s, with subsequent phases in the late ’50s, the ’60s, ’70s, and now, we are in the fifth phase, which began in the early 2000s and has lasted for over two decades. The fact that this is the fifth phase of insurgency highlights that the state has not addressed the aspirations or deprivations of the Baloch people, and this issue applies to other ethnic groups as well.

What’s interesting, though, is the emergence of new ethno-political movements that are challenging the state on their own terms. These movements, often led by the younger generation, are becoming more assertive. For instance, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM), which originates from the border regions of Pakistan and Afghanistan, has grown increasingly vocal. Just recently, in October, the PTM held a major gathering, where they issued an ultimatum to the Pakistani state. They demanded the removal of both the military and militants from the tribal peripheries. They gave the state two months to act, or they threatened to take matters into their own hands.

There has neither been a solution-oriented approach from the state nor a meaningful shift in policy. The state has failed to address the root causes of the violence. In Balochistan, leaders like Dr. Maran Baloch, who are focused on issues like enforced disappearances, face state responses that dismiss them. The chief minister of Balochistan and other officials have claimed these movements are driven by foreign agents, like India or Afghanistan, instead of recognizing the legitimate grievances of the people.

If there had been any meaningful solution, we wouldn’t still be seeing the fifth phase of the Baloch insurgency. The state’s failure to acknowledge and address the root causes of these movements only perpetuates the violence and instability.

AQ: Does that same lack of government response apply to other minority groups in Pakistan, like Hindus, Christians, Shias, and Ahmadis?

FS: Yes, though there are some differences. Hindus and Christians, for example, make up a very small portion of the population, so they aren’t as politically mobilized as some other groups, like Sindhis, Baloch, or Mohajirs. Additionally, issues of class and status also impact their political voice. The largest Hindu population in Pakistan is concentrated in Sindh, but there’s limited political power or mobilization among them.

One major issue affecting religious minorities, particularly in Sindh, is forced conversions—mainly of Hindus to Islam. This has sparked growing concern, yet it continues without effective intervention from the government. The state’s reinforcement of a “majoritarian” mindset, particularly through laws like the blasphemy law, severely impacts religious minorities. For instance, just last year, over 20 churches were burned in Faisalabad alone. These attacks on minorities are happening more frequently, and the state’s response remains inadequate.

This majoritarianism doesn’t just harm minorities; it affects the majority population as well. According to a study by a local think tank, between 1947 and 2021, over 1,000 Muslims were accused of blasphemy, alongside around 150 Ahmadis and about 100 Christians. This data reveals that the blasphemy law is not only a tool against minorities but is also misused for personal vendettas within the majority community.

AQ: How are Pakistan’s blasphemy laws being weaponized?

FS: Till date, no one has actually been executed under Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, though many Muslims, as well as others accused of blasphemy, are serving lengthy jail sentences, including life imprisonment. Many of these individuals endure desperate conditions, waiting for years as their cases continue in the courts.

Adding to the issue, there’s a troubling rise in vigilante activity related to blasphemy. For instance, there are groups that manipulate this situation—they’ll send blasphemous messages to trap someone, pretending they’re from that person, then report them for “blasphemy.” Such cases have surged over the past few years, turning blasphemy accusations into a kind of industry. Some of these vigilantes are motivated by financial gain, while others treat it as a “mission” to defend the prophet’s sanctity. It’s a deeply worrying trend, one that adds an extra layer of fear for anyone accused.

AQ: You mentioned that some people exploit the blasphemy laws for monetary purposes. Are these individuals or groups funded by local leaders or religious figures to advance a particular agenda?

FS: No, I don’t think local governments or officials directly fund these groups, but there’s certainly a lot of informal support. In Pakistan, there’s a strong cultural emphasis on charity — through sadka and zakat — which are religious forms of almsgiving. Many people donate generously to these groups as part of their religious obligations, oftentimes with little awareness of where the funds might go. While it’s not institutionally organized or directed by political figures, these groups manage to fund their activities independently through community donations.

It’s different from, say, India’s BJP, where hate crimes have been shown to increase in regions where they’re more influential. In Pakistan, the funding doesn’t stem from mainstream political channels; rather, these groups tap into religious donations and public goodwill.

AQ: How do traditional media and social media differ in their coverage of ethnic and religious minorities in Pakistan? How has this shift affected public discourse, especially regarding state criticism and minority issues?

FS: Traditional media tends to shy away from deeply analyzing ethnic minority issues — especially those surrounding groups like the Baloch or Pashtuns — focusing instead on broader, mainstream topics like democracy and civil-military relations. While there are occasional editorials that encourage empathy or critique the state’s treatment of minorities, they’re sporadic and lack sustained attention.

Social media, however, tells a very different story. It’s become the space where more critical voices—particularly among ethnic minority leaders and activists—can express themselves freely, often amplifying their perspectives far beyond what is possible in traditional outlets. Groups like the Baloch, Pashtun, and Sindhi activists, for instance, have used platforms like Twitter/X to voice grievances and even share insurgent activities, including videos of confrontations or statements from militant leaders. In this environment, information spreads quickly and is harder to regulate, forcing the state to impose restrictions like the “informal ban” on X, which many now access only via VPNs.

On platforms like TikTok and X, religious-political groups such as Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) have become quite sophisticated, using social media to spread their views and engage younger audiences. The TLP, among others, has adapted to digital influence in ways that traditional media wouldn’t allow, thereby amplifying their reach and impact. This heavy social media presence also reveals the state’s vulnerability in controlling the narrative. Social media has heightened public discourse and is reshaping the way the military and the government are viewed—now, much more critically.

AQ: Given the growing influence and vote share of the TLP, do you think the lack of strict enforcement on hate speech regulations has allowed groups with a sectarian or extremist leaning to solidify their presence and mainstream appeal? How does this wavering stance from the government affect not just minorities but the broader social and political climate in Pakistan?

FS: The inconsistency in the government’s approach has allowed such groups to grow and legitimize themselves within the political system. When the government briefly banned TLP in 2021, it was an attempt to curb their hate-driven rhetoric, which had led to incitement of violence, particularly targeting minorities. However, just six months later, the ban was lifted. This reversal seemed to be motivated more by political calculations than by a genuine commitment to curb hate speech or extremism. TLP’s growing popularity, as you mentioned, speaks to the broader consequences of this inconsistency. They are now the fourth-largest political party in terms of votes, despite only holding a provincial seat.

The lack of consistent action against hate speech means that groups like the TLP not only continue to operate but also gain influence and traction with voters. This has two main effects: First, it normalizes a discourse that is hostile to ethnic and religious minorities. Their rhetoric resonates with a particular base, and by failing to enforce hate speech laws, the state indirectly endorses this divisive ideology. Second, the state’s reluctance to implement these laws creates a broader environment where extremism can thrive without challenge, which ultimately undermines social cohesion.

This wavering approach from the state has also fueled distrust in the legal and political systems among minorities and marginalized groups. When groups like the TLP are allowed to operate freely despite their history of inciting violence, it signals to minorities that their safety is secondary to political expediency. This inaction only deepens sectarian divides, perpetuates fears, and reinforces an atmosphere of marginalization. Over time, this not only threatens social harmony but destabilizes Pakistan’s political framework by allowing extremism to increasingly influence the country’s political and social spheres.

AQ: How are online hate campaigns in Pakistan connected to real-world violence against minorities?

FS: Hate and incitement can spread just as powerfully by word of mouth as they do online.

Dr. Shahnawaz, a Muslim in Umerkot, Sindh was accused of sharing blasphemous content on his Facebook account, which he denied, claiming he didn’t know how it was posted. Yet, as the story spread, people grew angry, and he eventually had to go into hiding. But even in Karachi, where he had fled, the police picked him up, and he was killed in their custody. It’s unclear whether he was set up, but the result was deadly.

Then, there’s the 2017 case of Mashal Khan at Abdul Wali Khan University in Mardan. He was a progressive student who criticized university policies, and soon rumors spread that he had committed blasphemy. He had a secular mindset, which may have fueled the allegations, and ultimately, he was killed on campus by a mob.

So yes, these hate-driven incidents often spiral from false accusations or rumors that spread online and offline, and they lead to real violence in Pakistan. And while I don’t know as much about the dynamics in India, Pakistan’s examples show how serious this issue can be when accusations and hate campaigns go unchecked.

AQ: How does this kind of news usually spread? Is it more by word of mouth or through platforms like WhatsApp?

FS: Yes, it’s all of that — social media, WhatsApp, organized groups on various platforms, even TikTok, Facebook, X. These are all highly effective mediums for spreading this kind of news, along with word of mouth. For instance, in 2021, there was a case where a Sri Lankan factory manager in Pakistan was accused of blasphemy simply because he removed a sticker from a wall that mentioned the Quran. This incident spread quickly by word of mouth, mobilizing locals, who then took to the streets and killed him.

The most recent example was Dr. Shahnawaz. After his death, when his body was brought back to his village for funeral rites, people showed up and set his corpse on fire during the prayers. It’s a shocking reality. His body was partially burned by the mob, just a sign of the intensity of anger and mob mentality that we’re seeing.

In India and in Pakistan, the mob mentality spreads quickly, and the consequences are tragic and violent.

AQ: What sort of response do authorities have to individuals or groups who may propagate anti-minority hate? Are there any bans or restrictions on their activities?

FS: The issue in Pakistan is not so much the lack of laws but rather the weakness in their regulation and enforcement. There are laws for federalism, power sharing, and provincial autonomy — these were designed partly to address the concerns of ethnic minorities. But while the laws exist, they’re often poorly implemented. The same goes for regulations on religious and political influencers who spread hate speech or incite violence.

Since the War on Terror and the rise of electronic and social media, we’ve seen a massive increase in Islamist influencers who now have their own TV channels, live broadcasts, and online platforms. Some of these individuals openly make inflammatory remarks against minority groups, yet face minimal consequences. Occasionally, the government takes action—for instance, it briefly banned the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) after their involvement in violent protests. But this ban was soon lifted under public pressure, showing how quickly the state retracts its decisions in the face of religious pushback.

There was a well-known incident during Imran Khan’s government. When he appointed Atif Mian, a Princeton-based economist of Ahmadi faith, to an advisory role, there were immediate and violent protests by religious groups like the TLP, who demanded his removal solely based on his religious identity. The government ultimately withdrew his appointment, illustrating a tendency to appease religious groups rather than confront them. This repeated concession under pressure shows how deeply rooted these influences are and highlights the state’s struggle to enforce its own decisions when faced with religious opposition.

AQ: What role, if any, does the state play in directly or indirectly supporting hate speech or discriminatory policies against religious minorities like Shias, Ahmadis, Hindus, and Christians?

FS: The state’s role is certainly significant in fostering an environment where discrimination can thrive. Take the blasphemy laws, for instance. These laws are often cited as a form of structural violence, creating a legal framework that enables persecution. The most glaring example is the Second Amendment of Pakistan’s Constitution, which declares Ahmadis as non-Muslims. This kind of structural violence is ingrained in the legal system, and it’s not something people can easily escape. For instance, Ahmadis rarely identify themselves as such because of the fear of persecution, both socially and culturally.

Now, regarding other religious minorities like Hindus and Christians, there are no explicit laws preventing them from joining the bureaucracy or military. They can hold positions of power within these institutions, though their numbers are relatively low. The real issue is not necessarily formal discrimination but the cultural and societal hostility that these communities face. There is a growing sentiment of cultural violence, where minorities are marginalized through societal attitudes.

When it comes to Shias, the situation is a bit different. Shia Muslims, who make up around 20% of Pakistan’s population, have historically been integrated into state institutions, including the military and bureaucracy. There are no overt discriminatory laws preventing them from holding significant positions in power. However, the Islamization process initiated during General Zia-ul-Haq’s regime in the 1980s did exacerbate tensions, and it created a sense of alienation among Shia communities.

Although Shias have not faced widespread physical persecution or mob violence like some other minorities—such as forced conversions against Hindus or the systemic targeting of Ahmadis—they still experience a kind of cultural distaste. There is a strong sectarian sentiment that exists at the societal level, which marginalizes them. But the level of persecution is not as intense or overt as it is for other groups.

AQ: How is religious majoritarianism and the rise of groups like the TLP influencing Pakistan’s younger generation?

FS: The government has started to appease groups like the TLP, to the point where they’ve normalized this kind of radicalism. It’s now become a part of Pakistan’s political landscape. Just last year, for example, they passed a law increasing the penalty for blasphemy from three to ten years. So, we are witnessing Pakistan in this state where extremism is being legitimized.

Now, when it comes to the younger generation, this is where it gets concerning. More than 60% of Pakistan’s population is under the age of 30, and groups like the TLP have a huge influence on them. I’ve interviewed young people who have been radicalized by watching videos on social media, particularly those of Khadim Rizvi, the TLP founder. These young people — university students, some with only a basic education, others in small businesses — feel a sense of purpose in their mission to protect the sanctity of the Prophet Muhammad. They often say that at some point in their lives, they just realized what their mission was, and that mission is to defend religious values at any cost.

It’s particularly strong in urban areas like Karachi, where the TLP has a lot of support among middle and lower-middle-class youth. And these are not people from rural areas; they’re from the cities, with a conservative political and cultural orientation. So, you’re seeing that they are getting easily influenced by these ideas.

The government has taken some steps, but it’s not enough. While they’ve passed laws and even convicted people involved in violence, they’re still not addressing the root causes of radicalism. In fact, the government has been known to suppress civil society protests that call for more tolerance, and they’ve responded with police brutality. So, there’s this tension where the state’s actions don’t really match up with its rhetoric. They’re trying to fight extremism on one hand, but on the other, they’re also making concessions to the very groups that promote it.

(Arshi Qureshi is a Research Fellow at the Center for the Study of Organized Hate’s Violence, Extremism, and Radicalization Program.)