Introduction

Once a word that commonly referred to the return migration of individuals to their countries of origin, “remigration” has been redefined and politically weaponized to advance an ethnonationalist agenda. On November 28, 2025, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security posted on X, “The stakes have never been higher, and the goal has never been more clear: Remigration now.” Earlier in the day, President Donald Trump had likewise included the phrase “REVERSE MIGRATION” in a post on Truth Social. These two posts, published only hours apart, signify the growing popularity of the term “remigration” and its associated policy proposals.

The concept of remigration originates from French author Renaud Camus, who also infamously coined the Great Replacement theory — a population replacement conspiracy which alleges that leftist politicians and the “globalist” elite are deliberately undermining birth rates in Western countries through increased non-white immigration levels in order to tip the demographic balance. Remigration, in parallel, refers to the mass deportation of non-white immigrants, regardless of their citizenship status. The phrase has become the latest call to action, viewed as a solution to the alleged denigrating effects of the Great Replacement. For the far-right, the Great Replacement is considered the diagnosis for society, while remigration is the prognosis.

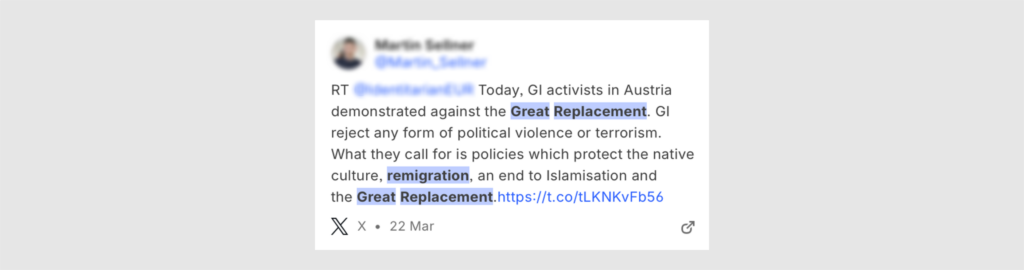

The term was quickly adopted by European far-right activists, specifically the pan-European Identitarian Movement, inspired by Camus’ writings during the 2010s. De facto Identitarian Movement leader Martin Sellner, author of the book Remigration: A Proposal, describes the enactment of a remigration agenda in Europe targeting migrants categorized into three different groups: illegal migrants (including applicants under the asylum process and temporary protection status); legal non-citizen migrants who hold a residence permit and/or work visa (but are considered “an economic, criminal, or cultural burden”); and “non-assimilated” migrants who have obtained citizenship (and are seen as “maintaining loyalty to foreign nations or radical religions,” i.e., Muslim-majority countries and Islam, respectively). Sellner proposes a centralized “assimilation monitor” database that includes details of migration backgrounds, crime rates, and social welfare benefits claims.

The remigration procedure is divided into three corresponding phases, tailored toward each target group. The first phase, occurring over a period of five years, calls for an immediate end to the asylum system and comprises strict border security measures, the repatriation of “illegal” migrants, political pressure on countries of origin, and the creation of “remigration cities” in North Africa to relocate asylum seekers. The second phase, spanning 10 years, focuses on immigration reform, including the termination of naturalization, a stringent review of visa holders, and the enforcement of a quota system. Taking place over the span of about thirty years, the third and final phase aims to secure long-term restoration of national and European pride and the reversal of the Great Replacement, including efforts towards “de-Islamization” (e.g., bans on minarets and the cessation of the foreign financing of mosques), and implementing return programs that offer migrants financial incentives for repatriation as well as the establishment of “remigration centers.”

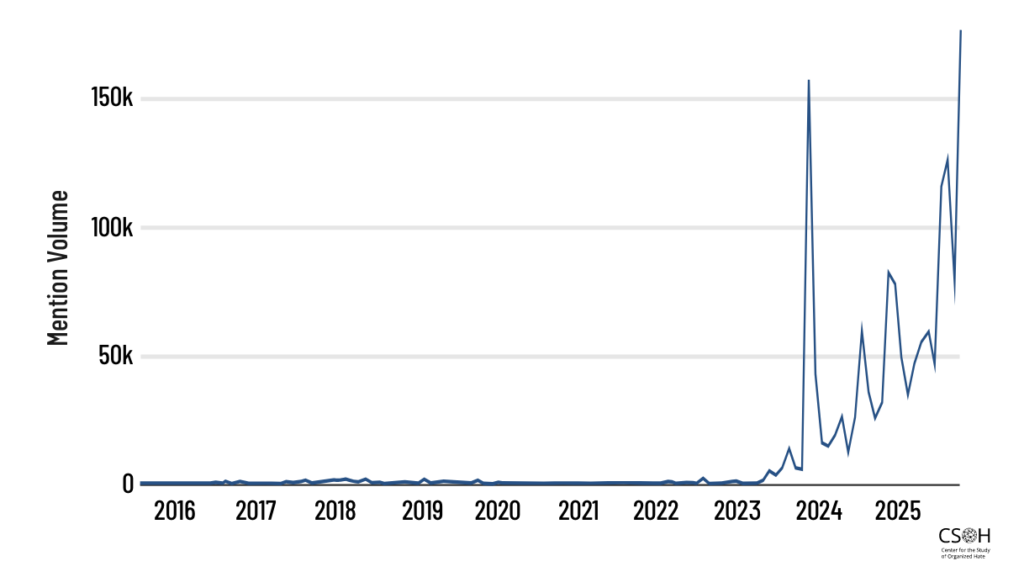

A once obscure concept, remigration has quickly gained traction in European — and, more recently, American — far-right circles, although its target groups and phases of adoption vary across these contexts. Nonetheless, the concept of remigration has become increasingly salient, particularly as a catch-all term signifying support for mass deportation, repatriation, and forced emigration. Remigration began appearing online in the 2010s but did not gain popularity until 2023–2024, subsequently reaching widespread visibility in 2025.

In 2025, remigration gained momentum within both grassroots and formal political arenas. The former is suitably encapsulated by the Remigration Summit held in Italy in May, featuring far-right activists and politicians attending from Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, Ireland, Portugal, France, Ireland, the U.K., and the U.S. In September, the Unite the Kingdom rally in London (which became an impromptu memorialization of the recently assassinated Turning Point USA founder Charlie Kirk), leveraged longstanding anti-immigrant rhetoric by displaying calls for remigration among attendees.

Remigration as a policy has also been backed by far-right parties across Europe in recent electoral campaigns. Notable examples include its embrace by the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) in September 2024, the Alternative for Germany (AfD) in the German election in February 2025, and the Forum for Democracy (FvD) and Conservative Liberals (JA21) in the October 2025 Dutch elections. Remigration is additionally supported by Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) in Belgium, League (Lega) in Italy, Vox in Spain, Alternative for Sweden (AfS) in Sweden, Finns Party in Finland, and Reconquest (Reconquête) in France. The euphemistic nature of the term has allowed it to be taken up more freely by these political parties, especially in Germany and Austria, where there is a strong association of the term “mass deportation” with the Holocaust. Crucially, these political parties lend normalcy to the concept and the proposed enactment of remigration in their manifestos, which is then legitimized by the democratic electoral process.

In the U.S., the Trump administration has likewise embraced a remigration agenda in both foreign and domestic policy by expanding the capacities of the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security. The swift institutional capture of a far-right idea with European origin signifies the development of a truly transnational movement rooted in shared anti-democratic and anti-egalitarian principles.

Against this backdrop, this report traces how the term remigration first appeared online in 2010 and rose in prominence over the subsequent fifteen years before gaining mainstream visibility in 2025. This analysis draws on a social listening tool to provide an overview of online posts mentioning remigration and the narratives driving engagement around the term. We observed that X (formerly Twitter) emerged early as the dominant platform for social media conversations about remigration. The platform’s affordances — e.g., algorithmic amplification, quote-tweeting, trending topics, and public engagement metrics — promote a performative environment in which content that generates outrage and public signaling is rewarded. Mentions of remigration often include sensationalist or fear-mongering discourse that creates a sense of urgency, frequently amplified by high-profile accounts on the platform.

We then compare these insights with a purposive sample of key Telegram accounts that align with the most influential accounts on X posting about remigration. In contrast, Telegram provides encrypted or semi-encrypted channels, asymmetrical broadcast structures (from administrators to followers), and minimal moderation, resulting in tightly curated ideological micro-publics. These differences in platform architecture influence not only the circulation of narratives but also the extent to which far-right actors strategically adapt their messaging to align with specific platform vernaculars. Through this cross-platform comparison, we demonstrate that Telegram operates as a medium to test the saliency of concepts like remigration, whereas X serves a strategic role in building broad support for the term across audiences in Europe and the U.S.

Key Findings

- Remigration narratives portray Muslim migrants as a demographic threat to white European societies, framing them as incompatible with Western culture and values. These narratives link Muslim migration to fears of “Islamization” and Islamist terrorism, promoting moral panics about an existential threat to Europe.

- Interpretations of remigration have evolved to adapt to different geographical contexts, especially from Europe to the U.S. where remigration is most often directed towards (particularly undocumented) migrants and used as justification for ongoing Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) deportation efforts. The transnational architecture of social media has made the exchange of ideas around remigration highly visible and rapidly scalable.

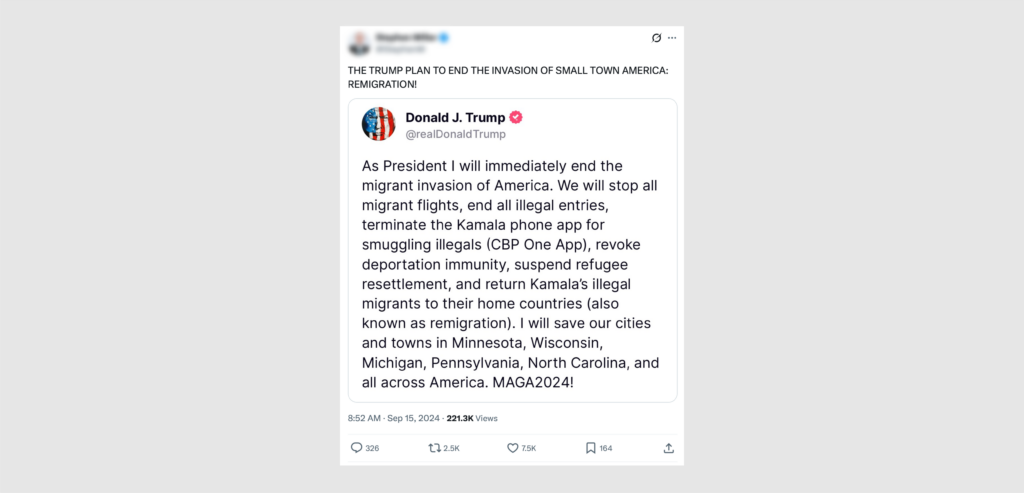

- Mentions of remigration first began appearing online in 2010, with Dutch far-right politician Geert Wilders an early adopter in 2012. It did not receive significant traction until 2016, coinciding with the emergence of ISIS and the refugee crisis in Europe. Thereafter, there were 32,000 mentions of remigration from 2016 to 2022 on X.

- Between 2023 and 2025, the volume of posts referring to remigration significantly increased, with the largest surge in activity occurring between September 2024 and December 2025, with 498,000 mentions originating from 198,000 unique authors on X.

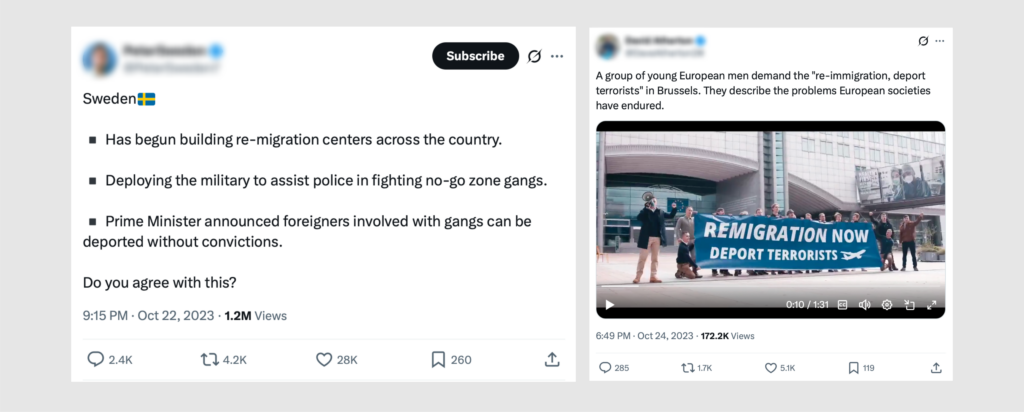

- The first major spike in mentions of remigration since the term first appeared online occurred in October 2023, with 13,000 total mentions originating from 9,822 unique authors on X. This can be attributed to two separate incidents: a viral tweet claiming that Sweden was building “re-migration centers across the country”; and high-profile accounts posting in support of a staged demonstration by Identitarian Movement activists outside the European Parliament calling for remigration.

- 2024 witnessed a dramatic surge in online activity referring to remigration, with 467,000 total mentions originating from 133,000 unique authors. The term’s virality peaked in 2024 from September to October, with the largest volume of posts correlating with the Austrian Freedom Party’s (FPÖ) election victory.

- In 2025, remigration gained mainstream visibility. Throughout the year, it had received 952,000 total mentions originating from 303,000 unique authors. The biggest spikes in mentions occurred in three waves: January to February (43,000 mentions), September to October (243,000 mentions), and late November to December 2025 (172,000 mentions).

- The highest number of online mentions of remigration ever recorded occurred in the week of September 1-8, 2025, totaling over 71,000. This surge in overall volume of content can be attributed to a few high-profile figures posting in succession on the same day: X CEO Elon Musk, Dutch far-right activist Eva Vlaardingerbroek, and Flemish far-right activist and former Vlaams Belang politician Dries Van Langenhove. Their viral posts collectively promoted the idea that the public sphere is dangerously overrun by violent “foreigners” committing crimes against the white majority population, and remigration is a necessity for public safety.

Methodology

The report uses a mixed-methods approach to content analysis to examine how the term remigration has evolved over time. We examine the use and amplification of the term across online sources from 2010 to 2025 using a social listening tool, drawing on purposive sampling from X (Twitter) and Telegram. Data was collected using a keyword-based query that captured explicit mentions of remigration as well as related framing keywords. The following keyword search was used to identify narrative trends and patterns associated with remigration:

( “remigration” | “re migration” | “re-migration” | “reimmigration” | “re-immigration” | “remigrations” | “re-migrations” | “remigrate” | “remigrieren” | “remigratie” | “total remigration” | “mass remigration” | “forced remigration”) + (“great replacement” | “replacement” | “population replacement” | “illegal” | “illegal migrant” | “illegal migrants” | “non-assimilated” | “asylum seekers” | “migrants” | “non-white migrants” | “mass migration” | “invasion” | “naturalization” | “naturalized” | “delinquent” | “criminal foreigners” | “foreign offenders” | “imported crime” | “rape” | “Islam” | “Islamization” | “de-Islamization” | “Deislamisierung” | “no go zone” | “summer, sun and reimmigration” | “deportation airline” | “migrant flights” | “deport” | “deportation” | “repatriation” | “reverse migration” | “European again” | “eliminate multiculturalism” | “Save America” | “Save Europe” | “Save Germany” | “Make Europe Great Again” | “Office of Remigration” | “re-immigration ministry” | “Vision remigration” | “Junge Tat” | “Globalist agenda” | “AfD” | “Identitäre Bewegung” | “Action Radar Europe” | “generation remigration” | “refugee resettlement” | “reconquest” | “Reconquista” | “ethnic cleansing” | “white genocide” | “Boer lives matter”)

Although non-English translations of remigration (e.g., the German “remigrieren” and the Dutch “remigratie”) were included, we found that an overwhelming majority of posts consistently used the English term remigration. Based on our analysis, we interpret this choice to be a deliberate strategy to mainstream the term across diverse linguistic contexts, as discussed in our findings below.

Quantitative data were examined from 2010 onwards, marking the earliest appearance of the term remigration in the dataset. Aside from several noteworthy social media mentions between 2016 to 2022, the term became more prominent from 2023 to 2025. Observed spikes were analysed in-depth to assess discourse formation and amplification dynamics. To complement these findings on X, we conducted a qualitative analysis of six public Telegram accounts associated with far-right and Identitarian actors, each featured as the top accounts by engagement on X posting about remigration. To conduct a cross-platform analysis, a custom Python scraper using the Telegram API was used to collect posts from each channel, from the earliest available to the most recent (as of November 30, 2025). The dataset was then filtered by time frame and manually coded using the same keyword-based query.

Our aim was to examine narrative shifts within each Telegram channel, including frequently used keywords used in conjunction with remigration, as well as how Telegram posts correlated with spikes in activity on X. This type of cross-platform comparison of selected accounts provides key insights, which are discussed below. Our approach ensured analytical consistency across platforms, providing insight into how different platforms, in this case, Telegram and X, contribute to the framing of remigration over the period under analysis.

Analysis

EARLY PHASES OF ADOPTION (2010-2022)

The term remigration first began appearing online in the early 2010s in websites and chat forums, although its use was extremely rare and not yet clearly linked to the Identitarian movement, which promotes a far-right ideology rooted in ethnonationalism that frames immigration as an existential threat to European cultural and demographic identity. The initial concept of remigration was developed after the publication of Renaud Camus’ book Le Grand Remplacement (The Great Replacement) in 2011, which continues to be a central guiding text for the Identitarians.

One of the earliest proponents of remigration was Dutch far-right politician and leader of the Party for Freedom (PVV) Geert Wilders, whose 2012–2017 election manifesto included the statement: “Daarom moeten we stoppen met de immigratie van mensen uit islamitische landen. Remigratie is een schone zaak” (That’s why we must stop the immigration of people from Islamic countries. Remigration is a clean business). Soon thereafter, the term began to circulate in Dutch-language counter-jihad chat forums in the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as in right-wing alternative media op-eds and the comment sections of online newspaper articles, with this usage continuing into the mid-2010s.

In 2014, social media posts containing the term remigration began to emerge, although they were extremely limited in number and reach.

That same year, the leading American conservative outlet National Review notably reported on an anti-immigrant protest in Paris — attended by Camus himself — which featured signs that read “Immigration — Islamisation, Demain la Remigration!” (“Immigration — Islamization, Tomorrow the Remigration!”).

Only a few weeks later, the Lyon branch of the Identitarian Movement in France organized a social gathering featuring a self-defense workshop that aimed to train women and men to protect themselves from Muslim male migrants. The event was shared online by supporters, including on the world’s largest neo-Nazi internet forum Stormfront in a post on the Croatia subforum that expressed admiration for the Identitarians’ strategy to push for greater visibility of remigration. The uptake of the term within street demonstrations was also documented in the Netherlands, where the neo-Nazi Dutch People’s Union (NVU) party marched with banners that read “Nederland is overvol, geen immigratie maar remigratie” (The Netherlands is overcrowded, no immigration but remigration).

Throughout 2015 and 2016, the rise of ISIS and ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks coincided with the refugee crisis in Europe, creating conditions in which the idea of remigration began to gain momentum. In March 2015, the Belgian far-right Flemish Interest (Vlaams Belang) party pioneered a so-called “remigration campaign” 20 targeting “radical” Muslims by offering ten one-way plane tickets for “those who yearn for the Islamic caliphate.”

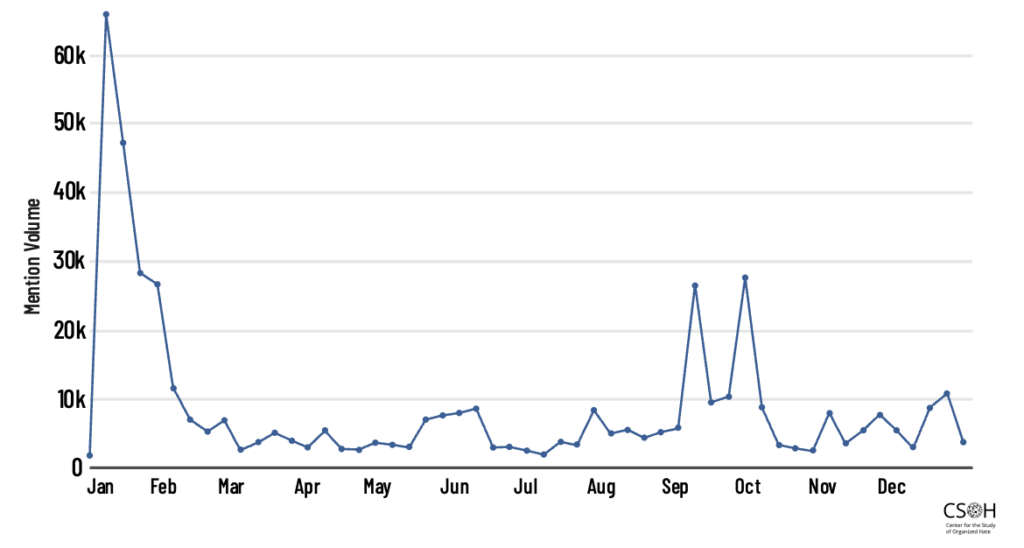

FIGURE 1. MENTIONS OF REMIGRATION ACROSS THE INTERNET FROM JANUARY 1, 2016 TO DECEMBER 31, 2025

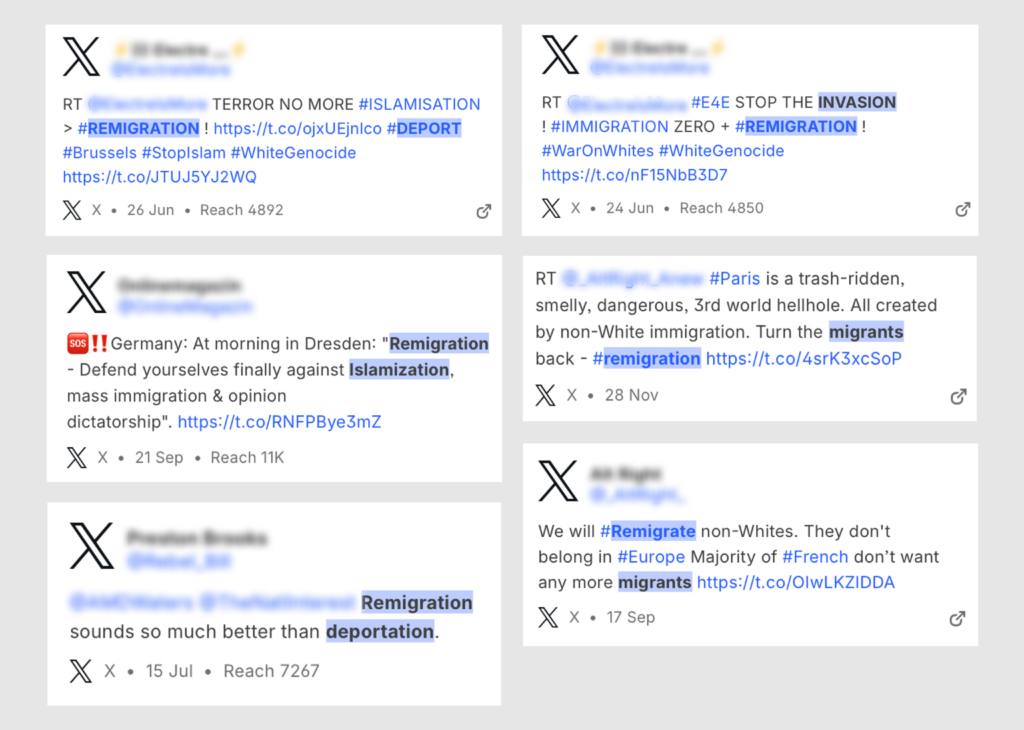

Remigration began circulating more visibly on Twitter in 2016 and 2017, with posts originating from bot accounts that promoted narratives linking Muslim migrants with “Islamization” and calling for their remigration. During this critical period, the term became closely associated with perceptions of Muslim migrants as a demographic threat to white European societies, framed as fundamentally incompatible with Western culture and values.

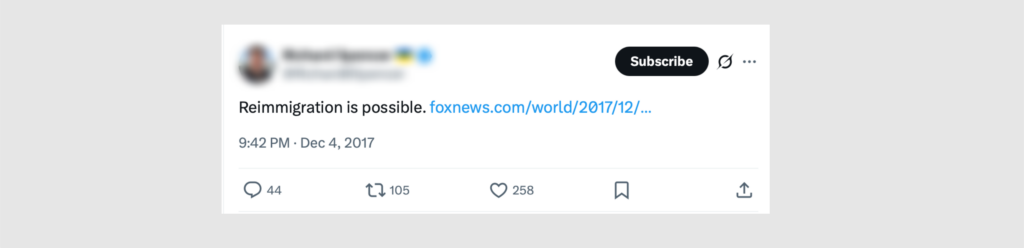

The term also circulated across North America during this period. In a notable offline incident, the far-right group Atalante Quebec displayed banners bearing “#remigration” at several sites housing asylum seekers across Quebec City and Montreal in August 2017. Around the same time, prominent American white supremacist and alt-right movement leader Richard Spencer posted that “remigration is possible” in response to a news article reporting that Germany was offering financial incentives for migrants to return to their countries of origin.

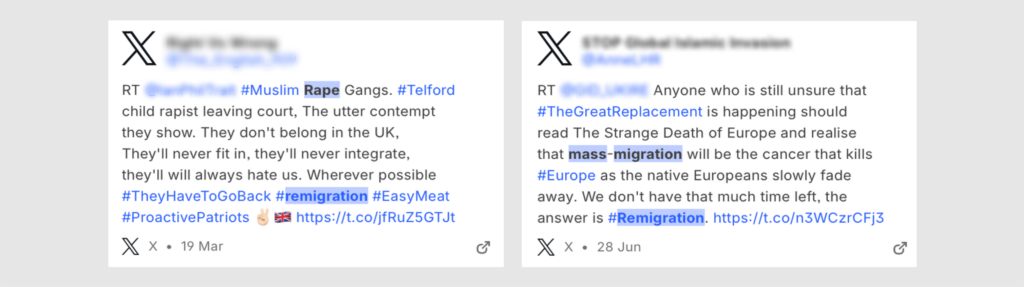

Although mentions of remigration had been increasing gradually since 2016, the term remained relatively dormant until small spikes in activity in March and June 2018. These increases coincided with court trials related to the ongoing “grooming gangs” scandal in the U.K., which had drawn heightened attention from far-right groups. Narratives portraying British Pakistani men as perpetrators of child sexual abuse and exploitation — primarily targeting young white British girls — circulated widely, framing Muslim men as rapists and criminals. Such discourse reinforced pre-existing Great Replacement narratives that represent Muslim and non-white migrants as hypersexualized, violent, and predatory. These characterizations would later shape discussions of remigration in relation to grooming gangs.

A key figure in debates surrounding remigration, Martin Sellner, posted the term on Telegram for the first time in 2018, writing:

“So after destroying communities through mass immigration and multiculturalism, which in turn acted as a breeding ground for terrorism, it is now these same, broken communities that are supposed to be able to stop it? #Remigration defeats Terrorism!” (Telegram, November 16, 2018)

At this point, the discourse reflects the adoption of securitized framing in which Muslim migrants are associated not only with demographic anxieties and conspiratorial messaging of “Islamization,” but also with the perceived threat of Islamist terrorism. In the wake of several ISIS-inspired attacks in Europe since 2015, ascribing such incidents as preventable risks to public safety acted as a mechanism of legitimacy while simultaneously promoting anti-Muslim hostility and stigmatization.

Meanwhile, a number of reactionary far-right political parties emerged in Europe in 2018, with stated opposition to Islam and immigration. This wave of newly founded or reformed parties quickly seized on the concerns of voters disaffected with the political establishment and claimed issue ownership on both immigration and integration. While remigration had not yet been widely incorporated into policy proposals, broader socio-cultural conditions and years of far-right digital activism laid the groundwork for its eventual adoption.

Later in 2019, one week after the Christchurch terrorist attack, the Identitarian Movement — whose ideology had influenced the shooter — held a demonstration protesting the Great Replacement and calling for remigration.

Despite efforts to distance itself from the Christchurch shooter, whose manifesto was titled “The Great Replacement,” as well as proclaiming that the organization “reject[s] any form of political violence or terrorism,” the Great Replacement theory had been circulating widely among far-right networks, largely due to the Identitarian Movement’s activism. The group subsequently shifted its focus to promoting remigration as a solution to the Great Replacement, framing it as a fully legal approach. By arguing that remigration could be achieved through nations’ exercise of sovereignty over their borders, the Identitarian Movement reframed the concept as a moderate and pragmatic proposal grounded in legal enforcement, obscuring its conspiratorial foundations.

From 2019 to 2022, mentions of remigration remained minimal, though relatively consistent. Usage of the term was primarily amplified by far-right accounts across Europe and the U.K., such as posts by Dutch PVV party leader Geert Wilders and the British Homeland Party, as well as several anonymous propaganda bot accounts.

Narratives associated with remigration continued to promote moral panics centered on defending Europe against the purported existential threat of Islam, which is presented as an “imported” problem resulting from migration. Similarly, discourse surrounding the grooming gangs scandal in the U.K. persistently misrepresented perpetrators as “Islamic child groomers,” thereby conflating pedophilic behavior with religious practices. Together, these fear-mongering narratives equate male migrants from North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia with the imminent dangers of Islamist extremism, sexual and physical violence, and organized crime.

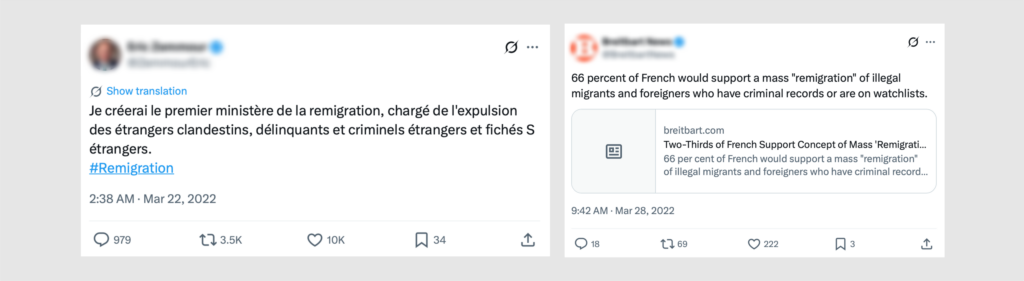

Significantly, in the run up to the French presidential election in April 2022, Éric Zemmour — candidate and founding leader of the far-right Reconquest (Reconquête) party — proposed a Ministry of Remigration with the aim to repatriate at least 100,000 “unwanted foreigners” annually.

This marked the first time a political party officially adopted remigration as a policy while proposing a dedicated government agency to implement it. The party’s name itself invokes the historical Reconquista, the period of Christian campaigns against Muslim rule on the Iberian Peninsula. A longtime proponent of the Great Replacement theory, Zemmour warned that “France will be a Muslim country by 2060” if current migration levels continued. While Zemmour ultimately lost the presidential bid, his proposal established the template for institutionalizing remigration through dedicated government infrastructure.

RISE IN POPULARITY (2023-2024)

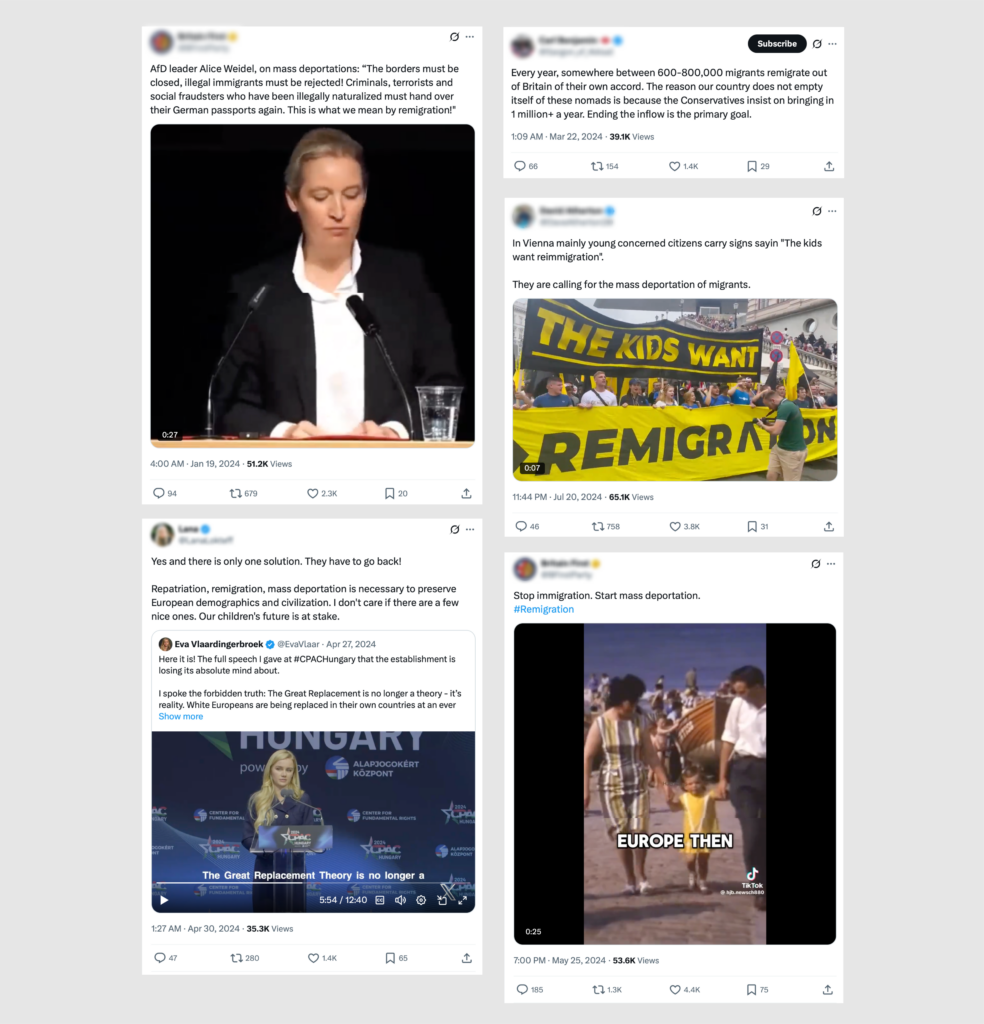

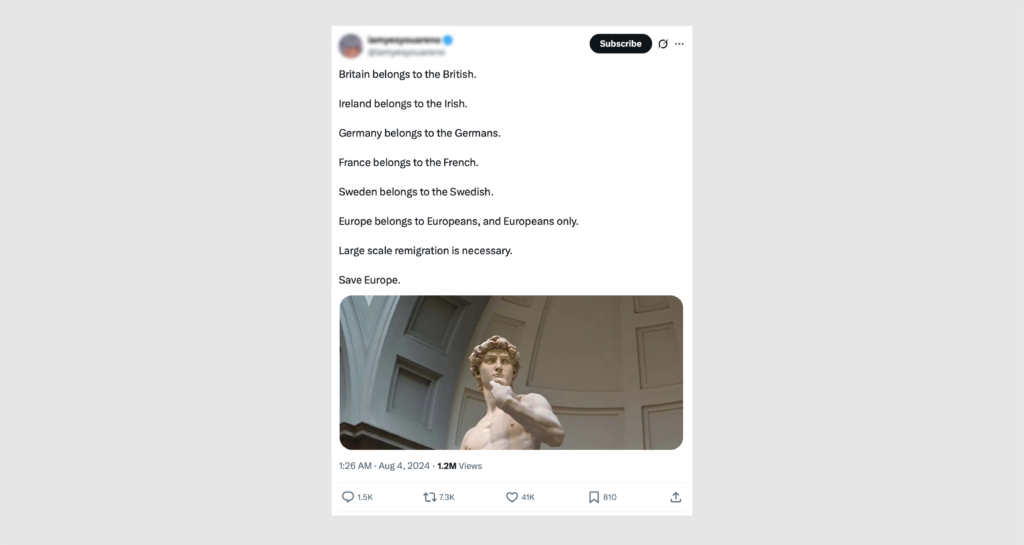

The first major spike in mentions of remigration since the term first appeared online occurred in October 2023, with 13,000 total mentions originating from 9,822 unique authors on X. This surge can be attributed to two key events: first, a viral but unsubstantiated tweet by Swedish far-right journalist Peter Imanuelsen, an early proponent of remigration since 2018, claiming that Sweden was building “re-migration centers across the country”; and second, positive reactions from high-profile accounts to a staged demonstration by Identitarian activists outside the European Parliament in Brussels, who called for “Remigration Now. Deport Terrorists.”

The discourse surrounding remigration reinforces the portrayal of migrants as criminals and terrorists deliberately seeking to “invade” Europe and “import conflict” from their countries of origin. Migrants from Muslim-majority countries are depicted as fundamentally incompatible with Western culture and societies due to alleged non-assimilationist behaviors and are framed as an imminent security threat of Islamist terrorism. Subsequently, Identitarian activists consistently blame the European Union for creating permissive immigration policies that prevent individual nation-states from exercising control over their borders due to the Schengen agreements.

That same October, pseudo-intellectual magazine The American Conservative published an article on “re-immigration” aspirations in Europe, introducing the concept to its U.S.-based audience. The article compares both the United States and Europe as facing “massive invasions by immigrants,” though it distinguishes between the two contexts. In the American case, immigrants were described as Christian, Latin American refugees from socialist countries with the potential to assimilate. In contrast, the article described “Moslems pouring across the Mediterranean into Europe” who are allegedly commanded by a religion that prohibits acculturation. “Re-immigration” is thus heralded as a solution promoted by European right-wing parties to “preserve European civilization” from “invaders.”

Overall, discourse about remigration in 2023 remained largely confined to far-right activists in Europe who promoted the concept in tandem with calls for urgency to end the Great Replacement and secure borders. However, the platform environment had shifted significantly. Following Musk’s acquisition and rebranding of Twitter to X at the end of 2022, content moderation weakened under the banner of “free speech,” while previously banned figures such as Martin Sellner returned to the platform. Coupled with algorithmic changes that amplified hateful and sensationalist content, these conditions resulted in the perfect storm for fear-driven messaging.

By comparison, 2024 witnessed a dramatic surge in online activity referring to remigration, with 467,000 total mentions originating from 133,000 unique authors.

FIGURE 2. MENTIONS OF REMIGRATION ON X IN 2024

A spike occurred in January 2024, when protesters gathered across cities in Germany following the publication of an investigative report by media outlet Correctiv. The report revealed that members of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) party’s Potsdam branch had secretly met with Identitarian Movement activists, including Martin Sellner, to discuss “remigration” plans to deport not only migrants but also German citizens with migrant backgrounds back to their ancestral countries. Despite widespread public backlash and the protests — some of which drew hundreds of thousands of participants — the AfD would eventually adopt remigration into its election manifesto for the 2025 federal election, likely emboldened by state-level election victories in September 2024.

During this period, we observed that transnational support for remigration began accelerating, indicated by increased posts from far-right political party, activist, and commentator accounts based in the U.K. and the U.S.

The same narratives expressing anti-migrant and anti-Muslim hostility pervaded. However, a subtle but significant shift emerged: the discourse increasingly focused on naturalized citizens of immigrant background, who were now also framed as threats. The notion of revoking citizenship based on ethnonationalist conceptions of loyalty not only establishes a dangerous precedent but also calls into question the legitimacy of democratic institutions and the rule of law.

A significant number of posts during this period also include the phrase “mass deportation(s),” which had not commonly appeared in conjunction with remigration in posts until 2024. The adoption and circulation of this phrase — given the association of mass deportations with the Holocaust — was initiated by prominent Anglosphere accounts before being embraced by European actors.

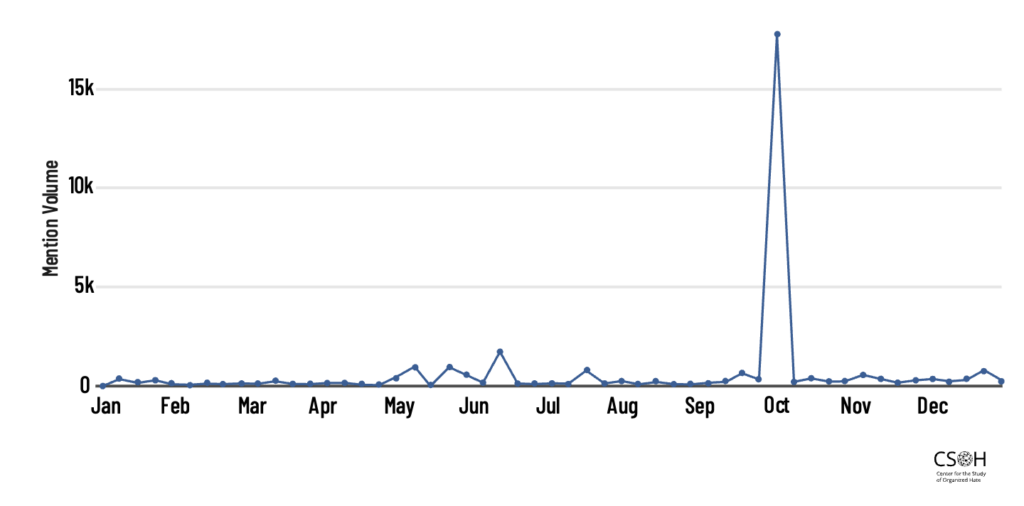

FIGURE 3. MENTIONS OF MASS DEPORTATION(S) ON X IN 2024

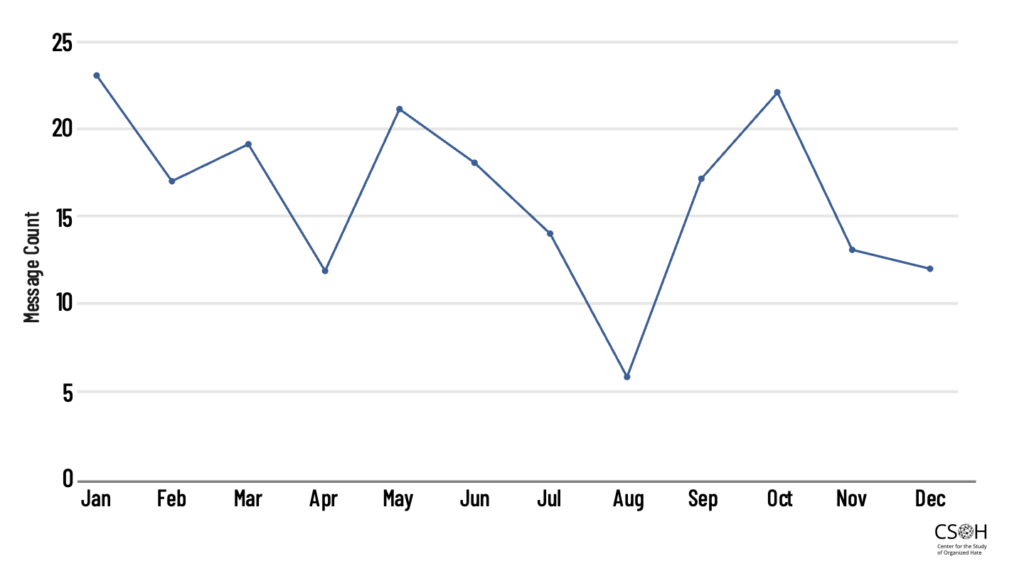

FIGURE 4. MENTIONS OF MASS DEPORTATION(S) ON TELEGRAM CHANNELS IN 2024

Our analysis reveals spikes in cross-posting about mass deportation between X and Telegram at key periods, namely, in January, May, and late September. Although these spikes do not always correlate across the platforms, it demonstrates that there a periods in which we see waves of similar activity. Thus, high-profile Telegram channels help drive the same conversation on X during spikes. Often, discourse begins to trend on Telegram prior to X. For instance, British far-right activist Tommy Robinson emerged as a key proponent of mass deportation, beginning to post the term on Telegram in 2022. Robinson singularly mentioned mass deportations 94 times between August 2024 and November 2025 on his channel. However, not until June 2025 did mass deportation reach widespread use with its articulation by President Trump in the context of ongoing Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids in the United States.

In general, mentions of remigration remained consistent before increasing once again online during the Southport riots across the U.K. from late July to early August 2024. During the riots, European Identitarian activists promoted a campaign titled “European Lives Matter” alongside photos of the victims of the Southport attack, proclaiming that “remigration saves lives.” Rampant misinformation surrounding the attack, combined with escalating anti-immigrant sentiment, created a flashpoint for mobilization, with remigration serving as a rallying narrative.

The term’s virality peaked in 2024 from September to October due to corresponding events. Most notably, the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) secured victory in the national election while openly campaigning on a platform favoring remigration. The largest volume of posts in 2024 correlated with the FPÖ’s election victory at the end of September.

The Identitarian Movement branch in Austria attributed the election outcome to years of strategic engagement and building popular support for the party’s agenda:

“💪The FPÖ’s election victory is the fulfillment of 5 years of education, action and resistance. All the patriots who spoke out, who took to the streets in the freezing cold against the corona dictatorship, have contributed to this.

Street and parliament, party and movement have won. Austria must become the country of reconquista and remigration.” (Telegram, September 29, 2024)

The Identitarians’ strategy relied on metapolitical activism focused on shifting public attitudes over the long term by emphasizing salient social and cultural issues in the realm of digital activism. The concept of remigration had thus emerged from sustained grassroots mobilization into fruition within the formal political arena — a development the movement lauded as a success.

At this stage, remigration had become a transnational far-right phenomenon. Tommy Robinson generously used the term, cross-posting the same message on X and Telegram in support of FPÖ. Meanwhile, the far-right news aggregate website Visegrád 24 reported that Sweden was implementing a remigration policy, claiming that migrants would receive financial incentives for repatriation.

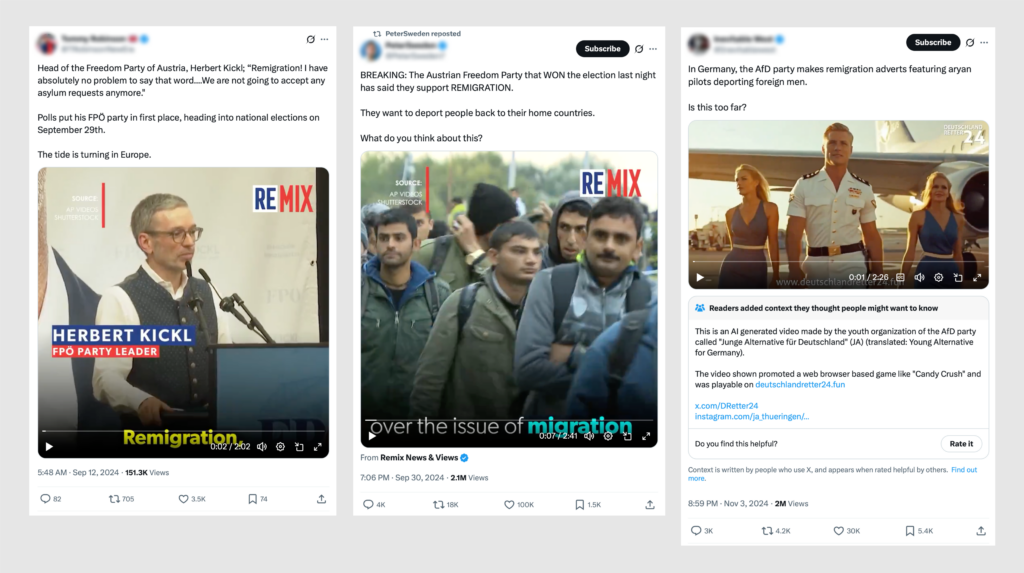

Only a couple of days after Visegrád 24 reported on news of the Swedish policy, then-presidential candidate Donald Trump and his political advisor Stephen Miller both posted their support for remigration in the run-up to the U.S. general election. Immigrants were positioned as unwelcome “invaders” intent on destroying the American cultural fabric of small, rural communities. Notably, mentions of Islam or Muslim migrants were omitted, indicating that remigration is a concept that can be recontextualized to fit differing interests and priorities. Within the MAGA movement, targets of remigration comprise broad groupings of immigrants who are collectively portrayed as a threat to white Americans. Thus, over the course of one year, the idea of remigration gained trans-Atlantic resonance, popularized through influential European and American figures.

MAINSTREAM PROMINENCE (2025)

In 2025, remigration gained mainstream visibility. Throughout the year, it had received 952,000 total online mentions originating from 303,000 unique authors. Three key significant spikes in posting activity occurred throughout the year: January to February (43,000 mentions), September to October (243,000 mentions), and late November to December 2025 (172,000 mentions).

FIGURE 5. MENTIONS OF REMIGRATION ON X IN 2025

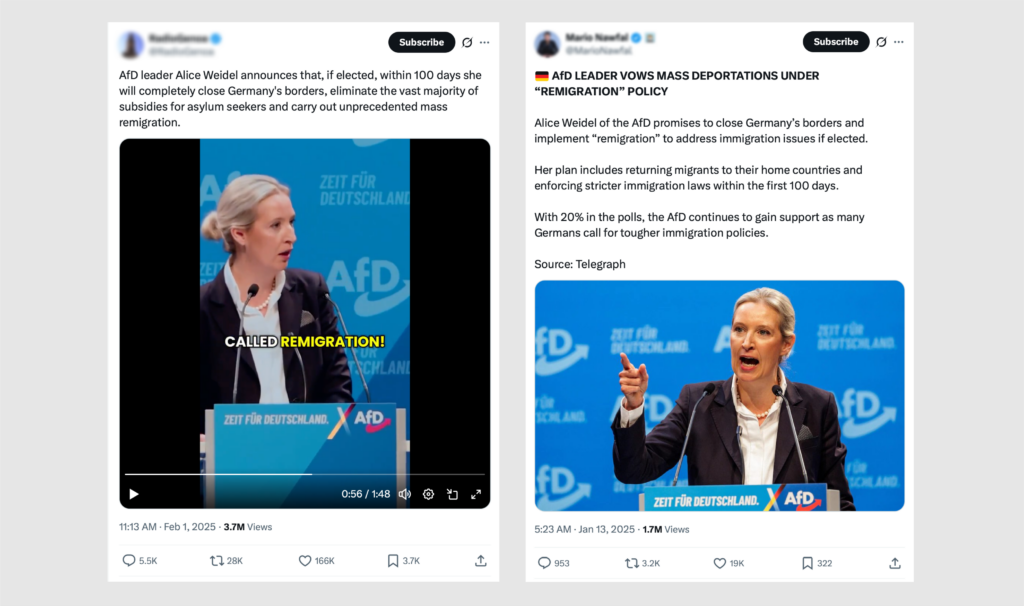

The German federal election on February 23, which resulted in a 20.8% vote share (the highest ever received) for the AfD, openly championing a remigration policy, accounts for the first spike, generating over 43,000 mentions. Social media posts celebrated AfD leader Alice Weidel’s openly stated commitment to close the country’s borders, restrict benefit claims for asylum seekers, and enact “mass remigration” efforts within the first 100 days in government. Video clips of the statements originated from the leader’s speech at the party conference in January, which marked the first time Weidel openly used the word “remigration” in public. Only a couple of days beforehand, Elon Musk livestreamed a chat with Weidel on X, using the social media platform to amplify the AfD’s message ahead of the election, including the narrative that Germany’s open borders allowed mass, uncontrolled migration into the country and the subsequent need for deportations.

Notably, we observed spikes in activity on Telegram channels prior to spikes in activity on X. For instance, Martin Sellner’s Telegram account mentioned remigration 24 times in early January, whereas a spike on X occurred in late January and early February. In the run-up to the German election, remigration became a mobilizing narrative on Telegram before it featured prominently on X. Thus, we contend that Telegram serves as a platform for in-group identity and community building in which mobilizing narratives are tested and reinforced among members of a channel with extremist views, whereas X is used for mainstreaming and achieving broader visibility aimed for public engagement. The strategic use of different platforms for cross-messaging relies on platform-specific affordances for ideological diffusion and engagement.

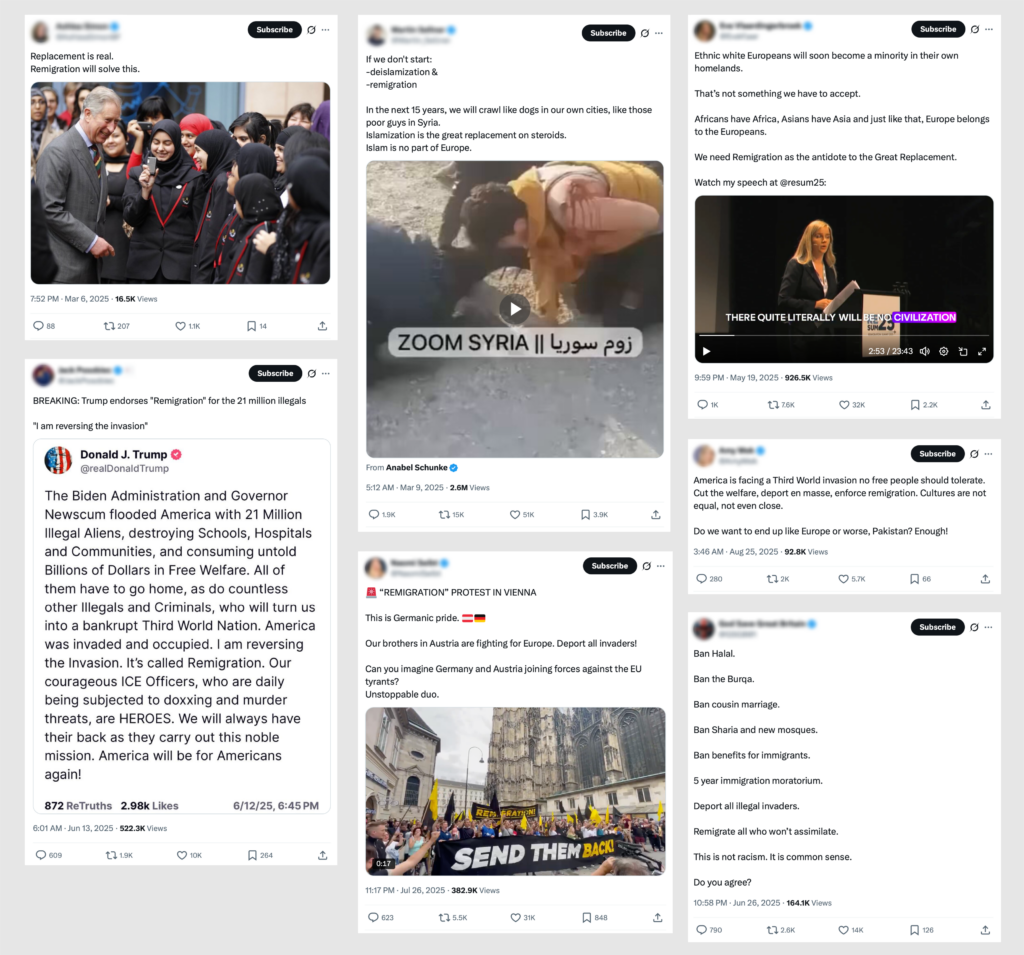

Between March and August 2025, mentions of remigration fluctuated between 5,000 to 16,000 posts monthly. Recurrent themes included depicting migrants as criminals or rapists, portraying Islam as an existential threat, and blaming politicians for enabling demographic destruction — collectively presenting a dystopic reality. By employing sensationalist tones and invoking moral panics, these posts by far-right activists and commentators call for urgent action in the form of remigration as a solution.

The descriptor “invasion” and its variant “invaders” were frequently employed across these posts, simultaneously dehumanizing migrants while invoking a sense of crisis. Within the United States, this discourse was appropriated to fixate on the constructed threat of rampant illegal immigration. In May, the Trump administration announced that the U.S. Department of State would create an ‘Office of Remigration,’ aimed at coordinating the return of non-citizens to their countries of origin. The proposed branch of the federal agency has yet to be fully implemented, but reflects a broader policy agenda of the administration that aligns with transnational European far-right interests, echoing Zemmour’s proposed Ministry of Remigration from three years earlier.

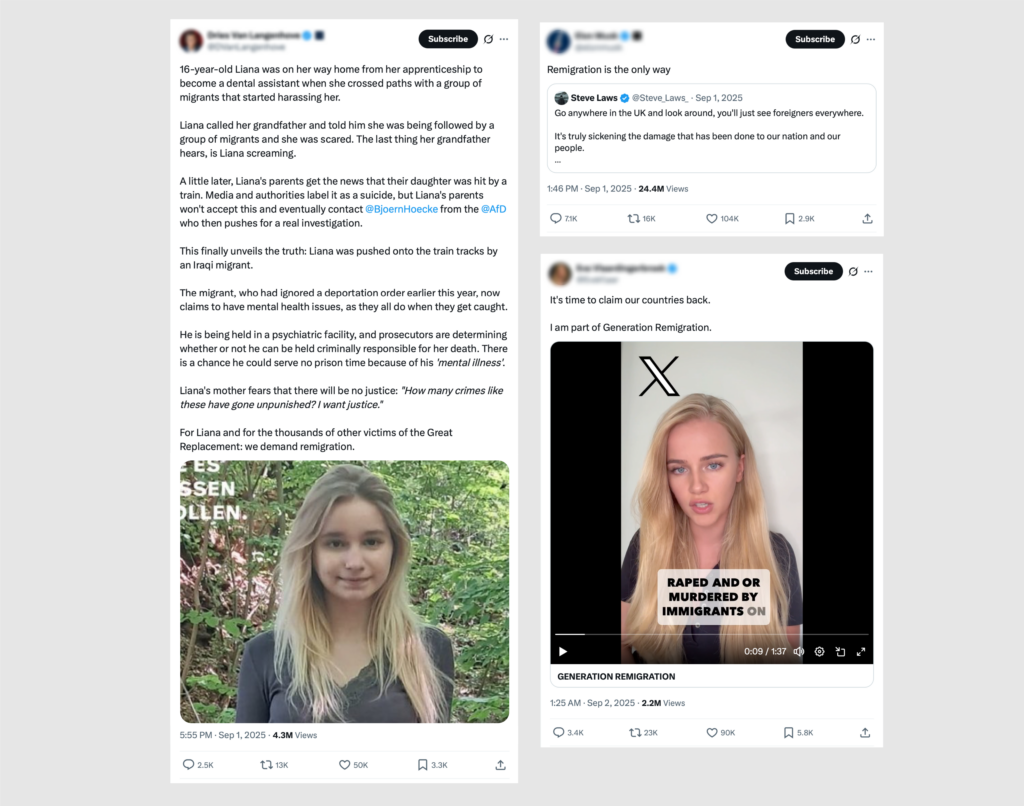

The second major spike in activity in 2025 occurred between September and October, with the highest number of mentions of remigration ever recorded in the week of September 1-8, totaling over 71,000. This surge in overall volume of content can be attributed to a few high-profile figures posting in succession on the same day: X CEO Elon Musk, Dutch far-right activist Eva Vlaardingerbroek, and Flemish far-right activist and former Vlaams Belang politician Dries Van Langenhove.

These viral posts share a common premise: that the public sphere is dangerous and fundamentally unsafe, allegedly overrun by violent “foreigners” intent on committing crimes against the white majority population. By constructing a narrative of collective victimhood rooted in fear, the posts deploy an emotional appeal that channels outrage and demands accountability. Within this framework, remigration is touted as a “logical” and necessary solution to perceived public safety threats.

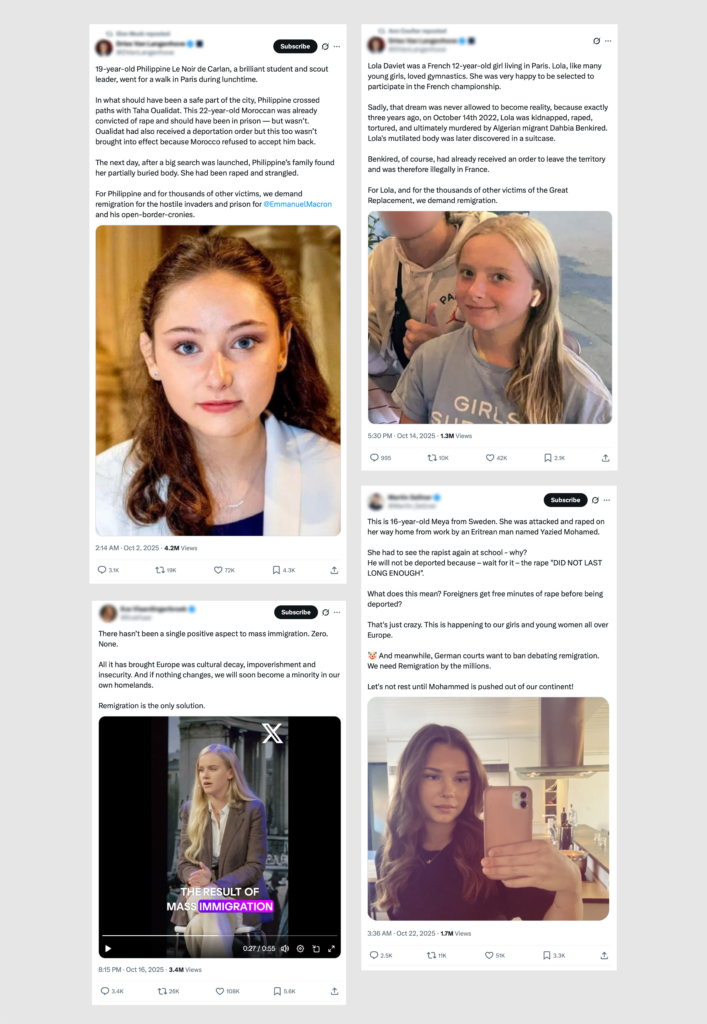

Following this initial surge, the term remigration remained consistently high throughout the remainder of the year, at times exceeding 45,000 mentions in a single week. Peaks in activity corresponded with the widespread circulation of sensationalist stories involving young white European girls allegedly subjected to sexual assault or violence by migrant Muslim men. These incidents — frequently presented as “evidence” — are leveraged to justify conspiratorial narratives such as the Great Replacement and the notion of “cultural decay”—a phrase cross-posted by Eva Vlaardingerbroek on Telegram and X. While many of these posts originated from European-based accounts, they were amplified by high-profile American users, significantly generating visibility for the term and its associated discourse.

Notably, during this period, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security posted a single word on X: “Remigrate.”

Although largely unfamiliar to most viewers, posting about remigration served a dual purpose. First, it acted as a signaling mechanism to an online MAGA base already familiar with far-right discursive norms, reinforcing a shared in-group identity. Second, because the post originated from an official government agency account, it functioned to cultivate public support for the administration’s actions and to legitimize national security operations through institutional authority.

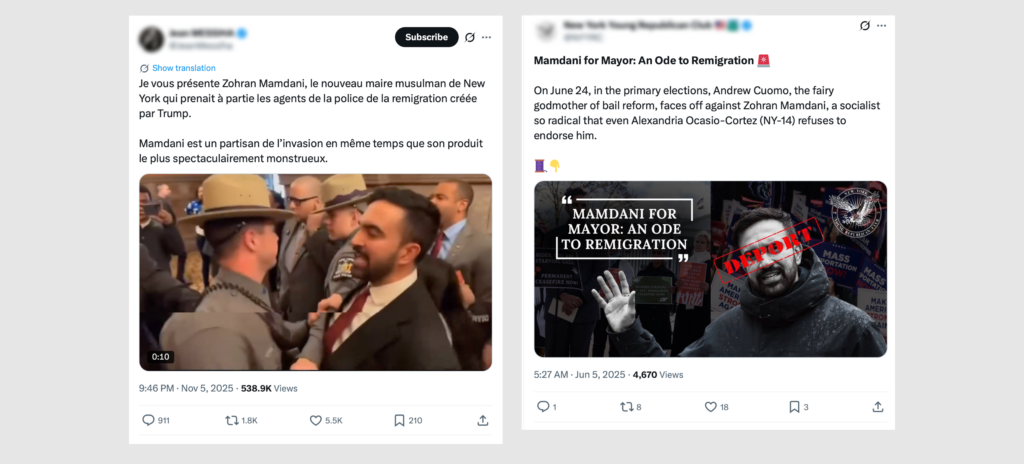

Within the U.S., mentions of remigration persisted throughout the off-year election period. As documented in our report on Islamophobic attacks and rhetoric targeting New York City mayoral-elect Zohran Mamdani, the term surfaced on X in calls for his deportation and denaturalization. These posts depicted Mamdani as a Muslim terrorist and portrayed him as a national security threat, deploying the language of counter-terrorism to justify his violent removal from the United States.

Toward the end of the year, a third spike emerged following November 26 in Washington D.C., in which an Afghan refugee wounded two National Guard soldiers, one of whom later died. Despite reporting that the perpetrator had previously served in a CIA-operated elite counter-terrorism unit and entered the U.S. through the Operation Allies Welcome resettlement program, President Trump and senior administration officials posted in open support of remigration in the immediate aftermath of the attack.

The administration moved swiftly, pausing issuance of visas for Afghan nationals, suspending decisions on pending asylum applications, and initiating a review of previously approved refugee status cases. These actions were legitimized through a remigration approach, framed not only as necessary national security measures, but as efforts to defend “Western civilization.” Within this discourse, primarily Muslim immigrants were constructed as fundamentally incompatible with American values, reinforcing civilizational binaries that cast migration as an existential threat.

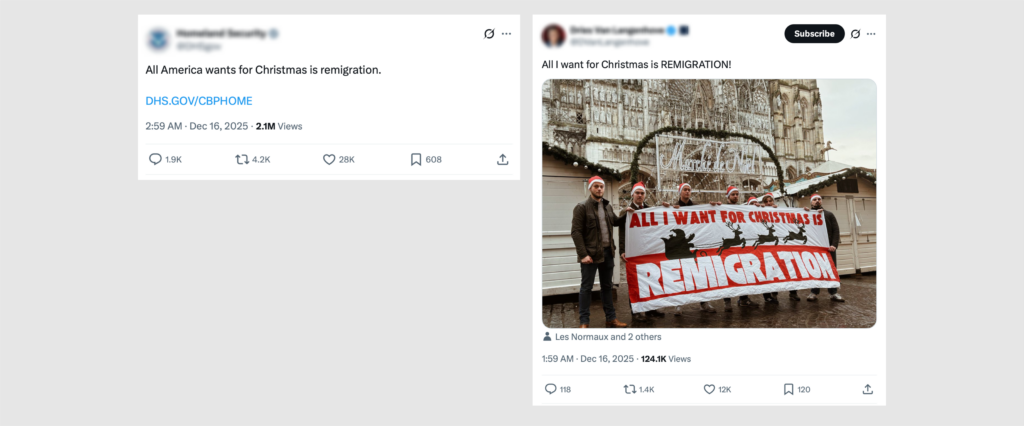

Finally, the end of the year saw a renewed reinforcement of remigration messaging when the U.S. Department of Homeland Security posted on X: “All America wants for Christmas is remigration.” The post links to a government webpage containing information about the U.S. Customs and Border Protection Home Mobile App, which is targeted at undocumented migrants who can choose “voluntary self-departure.” The app is described by the DHS as “a historic opportunity for illegal aliens to receive cost-free travel, forgiveness of any failure to depart fines, and a $1,000 exit bonus to facilitate travel back to their home country or another country where they have lawful status.” Individuals who submit documentation through the app indicating intent to depart the U.S. are allegedly deprioritized by ICE for detention and removal prior to their scheduled departure.

The humorous tone of the post sanitizes a concept often interpreted as a form of ethnic cleansing, trivializing policies that result in the dehumanization and mass expulsion of migrants. Soon thereafter, the message solidified as a meme, with prominent Belgian far-right activist Dries Van Langenhove posting the same day: “All I want for Christmas is remigration.” Similarly, the men’s nationalist club Second Sons Canada held a demonstration in Ontario with a banner reading “All I want for Christmas is remigration” while chanting “Ho ho ho, they have to go.” This rapid uptake illustrates how state-issued messaging can be easily absorbed into — and amplified by — transnational far-right ecosystems, further blurring the line between official policy communication and extremist propaganda.

Once a fringe concept circulating primarily among European far-right activists, remigration had, by the end of 2025, reached peak popularity in the U.S. From there, the term was re-exported back into European far-right ecosystems, reshaped through new rhetorical forms and political contexts.

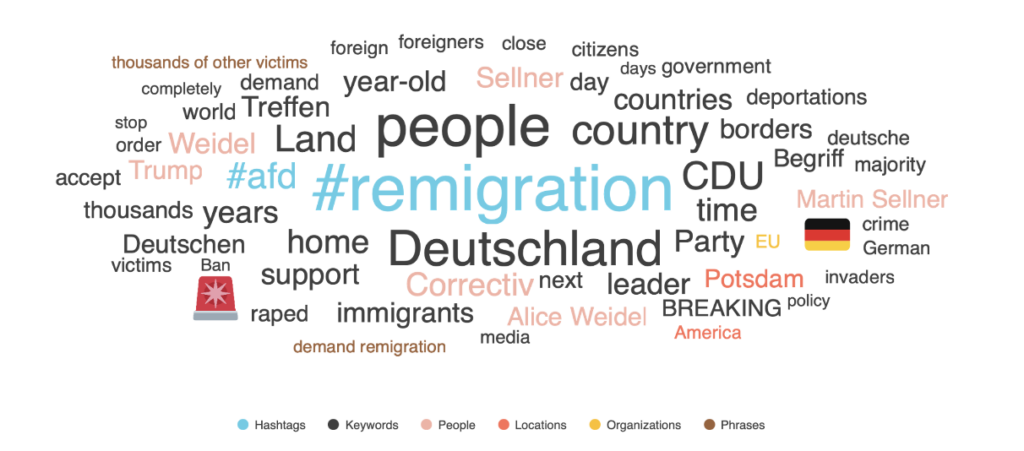

Word cloud for mentions of “remigration” on X (2024-2025)

In 2024, online conversations surrounding remigration largely centered on political developments within Europe, including electoral outcomes such as the Austrian Freedom Party’s victory. Over the course of the year, the term gained traction within far-right networks, where its usage functioned as an ideological signal, indicating shared alignment and in-group belonging to the respective audience.

By contrast, remigration discourse in 2025 shifted away from country-specific European developments (with the exception of the German election) and instead toward a more generalized narrative structure. Posts increasingly relied on keywords commonly associated with remigration rhetoric, including “immigrants,” “invaders,” and “foreigners” to describe target groups, alongside terms such as “raped” and “victims” to relate high-profile allegations of sexualized violence. While anti-migrant and Islamophobic tropes have long circulated within far-right discourse, the uptake of “remigration” serves a symbolic purpose: consolidating these narratives into a singular call to action that can be readily applied across disparate national and political contexts.

Conclusion

This report documents the emergence and rapid rise in popularity of the term “remigration.” Originating among European far-right ideologues in the early 2010s, the concept gradually expanded into a transnational phenomenon over the course of the 2020s before reaching peak visibility in 2025.

Our analysis of online content spanning the past fifteen years demonstrates that the term’s proliferation is driven by recurring narratives that depict migrants as criminals or rapists, frame Islam as an existential threat, and portray political leaders as complicit in demographic destruction. These narratives tend to intensify during moments of political salience (e.g., AfD’s success in Germany) or following violent incidents in Europe or the United States (e.g., cases of alleged sexual assault). These incidents are presented as “evidence” to support conspiratorial claims such as the Great Replacement theory. Remigration is consequently heralded as a radical yet necessary policy response to thwart perceived Western civilizational collapse. The positioning of remigration within a national security framework further imbues the concept with a sense of urgency and institutional legitimacy.

As a euphemism, “remigration” connotes a fundamentally anti-democratic and dehumanizing worldview. While the term originally developed as an expression of anti-Muslim hostility — galvanized by decades of Islamophobic mobilization — it has since evolved and adapted to new contexts to serve as a flexible tool of weaponization against other marginalized groups.

In Europe and the U.K., the primary target out-group continues to be Muslims with migrant backgrounds. Although the targeted communities vary by country, they largely encompass populations from North Africa, the Middle East, and South Asia, which are collectively conflated as an imminent threat of Islamist extremism, sexual and physical violence, and organized crime. In the U.S., by contrast, remigration is most often directed towards (particularly undocumented) migrants crossing the southern border — though this framing is not exclusive, as demonstrated by the response to the Afghan refugee incident. Within segments of the MAGA movement, especially among white nationalist adherents, any non-white migrant is considered validly exposed to remigration efforts. Despite these differing interpretations, political actors have increasingly weaponized the concept of remigration to advance policy agendas, often at the behest of a highly engaged grassroots base.

To date, remigration has primarily functioned as a central mobilizing narrative within far-right movements across the Global North. However, its adaptability suggests the potential to spread to the Global South as well. In parts of Southeast Asia, for example, exclusionary and dehumanizing rhetoric targeting Rohingya refugees continues to proliferate, creating fertile ground for remigration narratives. As this report demonstrates, the term’s malleability allows it to be easily recontextualized to suit new contexts. The transnational architecture of social media has made the exchange of ideas around remigration not only possible but highly visible and rapidly scalable.

Ultimately, this report serves as a case study in how a concept migrates from the margins to the mainstream. The concept of remigration may still be abstract to the general public, but its adoption and exponential embrace within political discourse is deeply concerning. The term’s uptake symbolizes an ascendent, globally connected far-right movement promoting an ethnonationalist vision that seeks to leverage the full power of the state in order to violently target and vilify migrants. Once a fringe concept, remigration has entered the highest levels of political office through deliberate strategies of repetition, institutional validation, and algorithmic amplification. Its ascent underscores the urgent need to scrutinize not only extremist actors, but the discursive pathways through which exclusionary ideas are rendered governable.

Download the full report here